VOICE

OF THE LANDSCAPE

A Palimpsest of Time and Place

Thomas Cole

Painter, Poet, Prophet

Earth Elegies III

Work-in-Progress

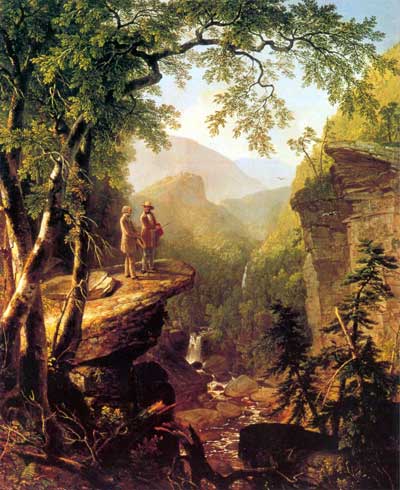

Kindred Spirits - Asher Durand

On the life of Thomas Cole

A funeral oration

Delivered before the National Academy of Design

New York, May 4th, 1848

By William Cullen Bryant

We who were not permitted to see our friend laid in his grave, and to pay his remains the last tokens of respect before they were forever removed from our sight, are assembled to pass a few moments in speaking of his genius and his virtues. He was one of the founders of the Academy whose members I address, as well as one of its most illustrious ornaments. During the entire space which has elapsed since the first of its exhibitions, nearly a quarter of a century, I am not sure that there was a single year in which his works did not appear on its walls; to have missed them would have made us feel that the collection was incomplete. Yet we shall miss them hereafter; that skilful hand is at rest forever. His departure has left a vacuity which amazes and alarms US. It is as if the voyager on the Hudson were to look toward the great range of the Catskills, at the foot of which Cole, with a reverential fondness, had fixed his abode, and were to see that the grandest of its summits had disappeared-had sunk into the plain from our sight. I might use a bolder similitude ; it is as if we were to look over the heavens on a starlight evening and find that one of the greater planets, Hesperus or Jupiter, had been blotted from the sky.

When the good who are not distinguished by any intellectual greatness die, we regard their end as something in the ordinary course of nature. A harmless life we say has closed ; there is one fewer of the kindly spirits whom we were accustomed to meet in our path ;-and save in the little circle of his nearest friends, the sole feeling is that of a gentle regret. The child dies, and we think of it as a blossom transplanted to brighter gardens; another springs and blooms in its place; the youth and maiden depart in their early promise, the old man at the close of his tasks, and leave no space which is not soon filled, But when to great worth is united great genius; when the mind of their possessor is so blended with the public mind as to form much of its strength and grace, his removal by death, in the strength and activity of his faculties, affects us with a sense of violence and loss ; we feel that the great fabric of which we form a part is convulsed and shattered by it. It is like wrenching out by the roots the ivy which has overgrown and beautifies and upholds some ancient structure of the Old World, and has sent its fibres deep within its masonry; the wall is left a shapeless mass of loosened stones.

For Cole was not only a great artist but a great teacher ; the contemplation of his works made men better. It is said of one of the old Italian painters, that he never began a painting without first offering a prayer. The paintings of Cole are of that nature that it hardly transcends the proper use of language to call them acts of religion. Yet do they never strike us as strained or forced in character ; they teach but what rose spontaneously in the mind of the artist; they were the sincere communications of his own moral and intellectual being. One of the most eminent among the modern German painters, Overbeck, is remarkable for the happiness with which he has caught the devotional manner of the old ecclesiastical painters, blending it with his own more exquisite knowledge of art, and shedding it over forms of fairer symmetry. Yet has he not escaped a certain mannerism; the air of submissive awe, the manifest consciousness of a superior presence, which he so invariably bestows on all his personages, becomes at last a matter of repetition and circumscribes his walk to a narrow circle. With Cole it was otherwise ; his mode of treating his subjects was not bounded by the narrow limits of any, system ; the moral interest he gave them took no set form or predetermined pattern ; its manifestations wore the diversity of that creation from which they were drawn.

Let me ask those who hear me to accompany me in a brief review of his life and his principal works.

Thomas Cole was born in the year 1802, at Bolton, in Lancashire, England. He came to this country with his family when sixteen years of age. He regarded himself, however , as an American, and claimed the United States as the country of his relatives. His father passed his youth here, and his grandfather, I have heard him say, lived the greater part of his life in the United States.

After a short stay in Philadelphia, the family removed to Steubenville, in Ohio. Cole was early in the habit of amusing himself with drawing, observant of the aspect of nature and fond of remarking the varieties of scenery. An invincible diffidence led him to avoid society and to wander alone in woods and solitudes, where he found that serenity which forsook him in the company of his fellows. He took long rambles in the forests along the banks of the Ohio, on which Steubenville is situated, and acquired that love of walking which continued through life. His first drawings were imitated from the designs on English chinaware; he then copied engravings, and tried engraving, in a very rude way we must presume, both on wood and copper. In 1820, when the artist was eighteen years of age, a portrait painter named Stein, came to Steubenville, who lent him an English work on drawing, treating of design, composition and color. The study of this work seems not only to have given him an idea of the principles of the art, but to have revealed to him in some sort the extraordinary powers that were slumbering within him. He read it again and again with the greatest eagerness ; it became his constant companion, and he resolved to be a painter. He provided himself with a palette, pencils and colors, and after one or two experimcnts in portrait painting, which were pronounced satisfactory, left his father's house on foot one February morning, on a tour through some of the principal villages of Ohio. From St. Clairsville, which he first reached, he wandered to Zanesville, from Zanesville to Chillicothe, and finally, after an absence of several months, during which he painted but few pictures, and experienced many hardships and discouragements, returned to Steubenville no richer than when he left it. In one of these journeys, that from Zanesville to Chillicothe, he walked sixty miles in a single day.

The family afterwards removed to Pittsburgh, and here, on the banks of the Monongahela, in the year 1823, he first struck into the path which led him to excellence and renown. The country about Pittsburgh is uncommonly beautiful, a region of hills and glens, rich meadows and noble forests, and charming combinations of wood and water, and great luxuriance and variety of vegetation. After the hour of nine in the morning, he was engaged in a manufactory established by his father, but until that time he was abroad, studying the aspect of the country, and for the first time making sketches from nature. Before the buds began to open, he drew the leafless trees, imitated the disposition of the boughs and twigs, and as the leaves came forth, studied and copied the various characters of foliage. I may date from this period the birth of his practical skill as a landscape painter, though I have little doubt that in his earlier wanderings on the banks of the Ohio, and perhaps in his still earlier rambles in the fields of Lancashire, he had cherished the close inspection of nature, and unconsciously laid up in his memory treasures of observation, from which he afterwards drew liberally, when long practice had given him the ready hand and the power of throwing upon the canvas at pleasure the images that rose and lived in his mind. In no part of the world where painting is practised as an art, does the forest vegetation present so great a variety as here; and of that variety Cole seemed a perfect master. I see in his delineations of trees a robust vigor of hand which leaves nothing to desire, and a diversity of character which seems to me almost boundless. Of this mastery and variety the picture which bears the name of the Mountain Home, one of his later works, is a remarkable example.

The business in which his father had engaged proved unsuccessful; it was abandoned, and late in the autumn of 1823 Cole took his departure for Philadelphia, with the design of trying his fortune in that city. The winter which followed was a winter of hardship and suffering, the particulars of which are related with some minuteness in Dunlap's book on American Artists. But he had youth on his side, and the hopes of youth, and a good constitution, and an unconquerable determination to excel, without which no artist ever became great. Between that determination and his acute sensitiveness there must have been many a hard conflict, but it prevailed. He obtained permission to draw at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, received some trifling commissions, struggled through that winter and the next, and in the spring Of 1824 joined his family, who had now removed to New York.

It was here that the public were first made acquainted with his merits, and that the day of his fame first dawned upon him. He had painted several landscapes, which were placed in a shop for sale. One of them was purchased by Mr. Bruen, an honorary member of this Academy, for a small sum, but the purchaser was so much delighted with it, that he immediately sought the acquaintance of the artist, and furnished him with the means of studying and copying the scenery of the Hudson. Three pictures were produced by him in the summer of 1824, which were exposed for sale at the price of twenty-five dollars each. They were purchased by three artists, I mention the fact with great pleasure,-three artists who generously and cordially acknowledged their merit, and continued ever after his friendsTrumbull, Dunlap, and Durand. " This youth," said Trumbull, when he saw them, "has done what I have all my life attempted in vain."

Two of the pictures of which I am speaking are in the exhibition opened for the benefit of his family since his death. They are not equal to his later works, but they arc skilful, faithful and original, and these qualities, once pointed out, made them the subject of general admiration. in one of the earlier editions of his poem entitled The Vanity of Human Wishes, Johnson thus enumerates the calamities incident to the life of a scholar:

Toil, envy, want, the garret and the jail.

Afterwards, when he had experienced what it was to possess a patron, he changed the line to:

Toil, envy, want, the patron and the jail.

Men of letters in the present age have luckily little to do with patrons; the community is their patron; the more general diffusion of education and of the habit of reading enables the man of decided literary talent to obtain from the people surer and more constant rewards than he formerly received from the bounty of the great. The painter, however, addresses himself to a taste much less generally cultivated than that of reading, and the works of his art are not, like books, in the power of every man to purchase and possess. He is therefore by no means secure from the misfortune of patronage.

It was the fate of Cole, at this period of his life, to meet with a patron. When his pictures first attracted the public attention, as I have already related, a dashing Englishman, since known as the author of wretched book about the United States, who had married the heiress of an opulent American family, professed to take a warm interest in the young painter, and charged himself with the task of advancing his fortunes. He invited him to pass the winter at his house, on his estate in the country, and engaged him to paint a number of landscapes, for which he was to pay him twenty or thirty dollars each, a trifling 'compensation for such works as Cole could even then produce, but which I have no doubt, seemed to him at that time munificent. It would hardly become the place or the occasion were I to relate the particulars of the treatment which the artist received from his patron, the miserable and cheerless apartments he assigned him, the supercilious manner by which he endeavored to drive him from his table to take his meals with the children of the family, and the general disrespect of his demeanor. These would have been a sufficient motive with Cole to leave the place immediately, but for the apprehension that his kind friends in New York, who had taken so strong an interest in his success, might ascribe this step to an instant temper, or to a character morbidly jealous of its dignity. He imposed upon himself, therefore, though deeply hurt and offended, the penance of remaining, labored assiduously at his easel, and executed several pictures which justified the high opinion his New York friends entertained of his genius. Fortunately, for a considerable part of the winter, he was relieved of the presence of his patron, who went to pass his time in the amusements of a neighboring city.

As early as he could finish the pictures on which he was engaged, he quitted the roof of the Englishman, and returned to Now York without payment for what he had done. Some time afterwards he compromised with this encourager of youthful genius, accepted half the compensation originally stipulated, and relinquished his claim to the remainder.

The works executed by Cole during this winter were sent by his generous patron as presents to his friends; they were samples of the talent which he had discovered, cherished and rewarded. One of the paintings in the present exhibition, is said to belong to this period of the artist's life. It is numbered 81 in the collection, a wild mountain scene, where a bridge of two planks crosses a chasm, through which flows a mountain stream. It has not the boldness and frankness, the assured touch, of his later productions, but it is full of beauty. There are the mountain summits, unmistakably American, with their infinity of tree-tops, a beautiful management of light, striking forms of trees and rocks in the foreground, and a certain lucid darkness in the waters below. The whole shows that Cole, amidst the discomfort and vexations which surrounded him, suffered no depression of his faculties, and that the vision of what he had observed in external nature came to him, in all its beauty, and remained with him until his pencil had transferred it to the canvas.

There had been no necessity of providing Cole with a patron. The public had already learned to admire his works under the guidance of those who were esteemed the best judges, and their attention being once gained, his success was certain. From that time he had a fixed reputation, and was numbered among the men of whom our country had reason to be proud. I well remember what an enthusiasm was awakened by these early works of his, inferior as 'I must deem them to his maturer productions, the delight which was expressed at the opportunity of contemplating pictures which carried the eye over scenes of wild grandeur peculiar to our country, over our aerial mountain-tops with their mighty growth of forest never touched by the axe, along the banks of streams never deformed by culture, and into the depth of skies bright with the hues of our own climate; skies such as few but Cole could ever paint, and through the transparent abysses of which it seemed that you might send an arrow out of sight.

In 1825 the National Academy of the Arts of Design was founded. This great enterprise, for such I must call it, was principally effected by the exertions of one who has since been lost to art, though translated perhaps, so far as the mere material interests of society are concerned, to a sphere of greater usefulness. I may speak of him, therefore, as an academician, as freely as if he had departed this life. In establishing the Academy he met with many obstactes and discouragements, but they gave way before his ingenuity and perseverance. " Do you know," said a friend of mine, scarce less highly endowed as a connoisseur than as a man of letters ; " do you know what Morse is doing among the artists ? He has made them lay aside their jealousies, and forget their quarrels ; he has inspired them with a desire to raise their profession to its proper dignity, and has united them into an association for the purpose."

At that time the New York Academy of the Fine Arts was in existence; it had Colonel Trumbull with his great reputation at its head, and numbered among its members nearly all the men of wealth in New York, who desired to be regarded as friends of the fine arts. The new association of artists, not satisfied with the manner in which it was conducted, nor with the opportunities it afforded to pupils, asked that a certain number of artists should be placed in the board of its directors. This demand, after some negotiation, was refused, and Morse led his band of artists boldly to the conflict with the old Academy and its opulent patrons. They founded the Academy of the Arts of Design, governed solely by artists; appealed from the patronage of the few to the general judgment of the community, and triumphed. The barren exhibitions of the old Academy, with their large proportion of casts and pictures which had been seen again and again, were deserted for the brilliant' novelties offered by the new, and finally the elder of the two rivals expired by a death so easy and unnoticed, that few, I suspect, now recollect the date of its dissolution.

The Academy of Design meanwhile has gone on with a constant increase of prosperity, presenting from year to year richer and more creditable exhibitions, though some, who have been rendered fastidious by what they have learned from these very exhibitions, absurdly maintain the contrary; it has gone on with an increasing revenue, till it is able not only to support an excellent school for the instruction of pupils of both sexes, but to pension the widows of the academicians.

Let me say a word or two concerning the artist I have just named, for many years the president of this institution, and worthy to stand at the head of an association of which Cole was a member. He possessed in a high degree all the learning and knowledge of his art. The bent of his genius was towards historical painting, in which various circumstances want of encouragement was the principal prevented him from taking that rank to which he might otherwise have raised himself. He was embarrassed somewhat by another obstacle; the turn of his mind was experimental, a quality more fortunate for a scientific discoverer than an artist, and he boldly trusted himself to new paths, in which perhaps he sometimes lost his way. Yet from time to time he would astonish the world with glimpses of the great powers which he possessed, and which only needed opportunity and steady exercise to mature them into their due strength and excellence. " I know what is in him," said the great Allston, in a letter to Dunlap, " better, perhaps, than any one else. If he will only bring out all that is there, he will show powers that many now do not dream of"

In that fraternity of artists which founded the Academy, was another man of genius who began his career almost at the same moment with Cole, and who closed it in death two or three years earlier. Inman, the first vice-president of the institution, was a portrait painter of extraordinary merit, great facility of pencil, a pleasing style of color, and a power of happy selection from the various expressions of countenance which a sitter brings to the artist. The versatility of his powers was surprising: he has left behind him specimens of landscape, of figures in groups, in repose or in action, which show that he might have excelled in any branch of the art. His view of Rydal Water, painted for one of our number, from a spot near the dwelling of the poet Wordsworth, is a picture of extreme beauty; a soft aerial scene, like a dream of Paradise; the little sheet of water seems one of the lakes of the Happy Valley, and the mountains are like hills of fairy land. He was not a man like Cole, to linger long in contemplation of the objects he would delineate, to study them till he had exhausted all they could offer to his observation, and till their image became incorporated with his mind. What he saw, he saw at a glance, and transferred it to the canvass with the same rapidity, and with surprising precision. His works owe nothing to revision, and possess a certain unlabored grace which makes us delight in reverting to them.

With such men, and others worthy to be their colleagues, Cole was associated in the early days of the Academy. At its first exhibition, in 1826, he contributed a snow-piece, not one of his most remarkable works, perhaps, but bearing the characteristics of his manner. He now received frequent commissions, and somewhat more than two years later, near the close of 1828, was enabled to gratify a desire which all artists feel with more or less strength, to visit Europe. He went first to England, where our countryman Cooper received him with kindness, and introduced him to the poet Rogers, who took much interest in him, and gave him a commission for a picture. The great portrait painter, Lawrence, behaved to him in a most friendly manner, but he died not long after his arrival. His residence in England does not seem to have been favorable to his serenity of mind. He complained of the gloom of the climate, accustomed as he had been, ever since he became an artist, to our brilliant skies, and the almost superabundant light of our atmosphere; and he was much affected by the coldness of the English artists, who saw nothing in his pictures to commend. Turner, with his splendid faults, his undeniable mastery in some respects, and his egregious defiance of nature in others, had taken possession of the public taste, and it was no easy matter for so true a painter as Cole, unsupported by the favorable testimony of those who were recognized by the public as judges of art, to obtain for his works an impartial consideration. He sent pictures to the public exhibitions in London for two successive seasons, and, though the subjects were American, they were hung in such situations that even his friends, familiar with his manner, could not distinguish them for his.

In May, 1831, he left England for Paris, hoping to be able to study awhile at the Louvre; but at that time its walls were covered with an exhibition of modern French paintings, of which he liked neither the subjects nor the treatment, and he proceeded immediately to Italy. It appears from a letter of his to Dunlap, that even after his arrival in that country, he found it hard to shake off the depression of spirits which kept possession of him during his residence in England. It left him, however, and he speaks with delight of his sojourn in Florence, which he calls the painter's paradise. He studied the noble collections of art which it contains, drew sedulously from life, and executed his Sunset on the Arno, and several other works. Many of those who hear me will probably recollect this picture, a fine painting, with the river gleaming in the middle ground, the dark woods of the Cascine on the right, and above, in the distance, the mountain summits half dissolved in the vapory splendor which belongs to an Italian sunset.

From Florence be went to Rome, where he had his studio in a house once occupied by Claude. He seems to have studied the remarkable and beautiful country in the neighborhood of the eternal city, scattered with ruins, and the fine effects of the Roman climate, even more than the objects contained in its magnificent repositories of art. Here he made sketches from which he afterwards painted some of his best pictures. Naples attracted him further south, and from Naples he made an excursion to Paestum. I used to relate that as he was preparing for a visit to the solitary temples, which are all that is left of that ancient city, he happened to speak of his design in presence of an Englishman who had just returned from them. Why do you go to Paestum ? " said the Englishman "you will see nothing there but a few old buildings." He went, however, saw the old buildings, the grandest and most perfect remains of the architecture of Greece, standing

"---between the mountains and the sea,"

in a spot where, in the beautiful words of the same poet,

"The air is sweet with violets running wild,"

but which the pestilential climate has made a desert; he saw and painted a view of them for an American lady.

While in Italy, the manner of Cole underwent a considerable change; a certain timid softness of manner in comparison I mean with his later style was laid aside for that free and robust boldness in imitating the effects of nature, which has ever since characterized his works. I recollect that when his picture of the Fountain of Egeria, painted abroad, appeared in our exhibition, this change was generally remarked and was regretted by many, who preferred the gentle beauty of his earlier style, attained by repeated and careful touches, and who were half-disposed to wish that the artist had never seen the galleries of Europe.

It seems to me, however, that the transition to this bolder manner was the natural consequence of his advance in art and of confidence in his own powers, and that it would have taken place if he had never seen a picture by the European masters. It is not unusual with men of powerful genius in any of the fine arts, that their earlier essays are marked with a certain graceful indecision, a stopping short of the highest effect, on account of some hesitation as to the means of producing it, or some fear of the manner in which it will be received. From this if they had never departed they could never have become great. With riper powers, higher skill and a knowledge of their own strength, they become impatient of commonplace beauty, and rise by a necessity of their nature to a more masculine method of treatment. Connoisseurs trace this change in the paintings of Raphael; critics in the poetry of Byron.

That Cole would have been a great painter if he had never studied abroad, scarcely less great on that account, no man can doubt. But would he have been able to paint some of these pictures which we most value and most affectionately admire; that fine one, for example, of the Ruins of Aqueducts in the Campagna of Rome, with its broad masses of shadow dividing the sunshine that bathes the solitary plain strown with ruins, its glorious mountains in the distance and its silence made visible to the eye? Would he have ever given us a picture like that which bears the name of The Present, a scene of loneliness, populous with the reminiscences of days gone by; or a picture like that great final one, the Course of Empire? Cole owed much to the study of nature in the Old World, but very little, I think, to its artists. He speaks in his letter of the delight with which he regarded the works of the older painters of Italy, on account of their love for the truth of nature, the simplicity and single-heartedness with which they imitated it, and their freedom from the constraint of system; but I see slight traces of anything which he could have caught from their manner. He had a better teacher, and copied the works of a greater artist.

Cole came back to America in 1832, recalled somewhat sooner than he wished by the ill health of his parents and their desire for his return. Within a year or two afterwards, he began the series of large pictures, so well known to the public under the name of the Course of Empire. I shall not weary those who bear me with any particular description of these paintings, which are among the most remarkable and characteristic of his works. The subject is finely conceived, and though the execution of each is not equal, they have all some peculiar excellence. The second, representing the pastoral state of mankind, ranks among his most pleasing landscapes; the fifth and last, placing before us the remains 'of a great city crumbling into earth, reclaimed by nature to nourish her vegetation and to furnish herbage for the flock, is one of those pictures which Cole only could paint. The third is an architectural piece of great splendor, with an imposing arrangement of stately structures ; the fourth, though the subject was not of that kind which he delighted to paint, is full of invention and energy, and the struggle between the host of the besiegers and the crowd of the besieged, is given in such a manner as to blend simplicity of effect with variety of detail. "'I have been engaged ever since I saw you," said he in a letter to one of his friends, " in sacking and burning a city, and I am well nigh tired of such horrid work. I did believe it was my best picture, but I took it down stairs to-day and got rid of the notion."

The Course of Empire, I find on looking over some of his letters, was not completed till 1836. It was painted for one of the most generous and judicious friends of art whom the country ever had, Luman Reed, who died before the artist had finished the series.

It was while he was thus engaged that he married and fixed his residence at Catskill, in a region singular for its romantic beauty, where the remainder of his life was as happy as domestic harmony, his own gentle and genial temper, and the love of those by whom he was surrounded, could make it. His genius had grown prolific as it ripened; and in this charming retreat he executed some of his noblest works. Among these I must class the Departure and Return, produced in 1837. There could not be a finer choice of circumstances nor a more exquisite treatment of them than is found in these pictures. In the first, a spring morning, breezy and sparkling, the mists starting and soaring from the hills; the chieftain in gallant array at the head of his retainers, issuing from the castle-in the second, an autumnal evening, calm, solemn, a church illuminated by the beams of the setting sun, and the corpse of the chief borne in silence towards the consecrated placethese are but a meagre epitome of what is contained in these two pictures. In both, the figures are extremely well managed, though in this respect he was not always so fortunate, nor did his strength lie in that direction. The two works which he named the Past and Present, produced in the year following, have scarcely less merit as a whole; the latter of them is one of those pictures, rich, solemn, full of matter for study and reflection, in producing which Cole had no rival.

In 1840 he completed another series of large paintings, called the Voyage of Life, of simpler and less elaborate design than the Course of Empire, but more purely imaginative. The conception of the series is a perfect poem. The child, under the care of its guardian angel, in a boat heaped with buds and flowers, floating down a stream which issues from the shadowy cavern of the past and flows between banks bright with flowers and the beams of the rising sun ; the youth, with hope in his gesture and aspect, taking command of the helm, while his winged guardian watches him anxiously from the shore; the mature man, hurried onward by the perilous rapids and eddies of the river; the aged navigator, who has reached, in his frail and now idle bark, the mouth of the stream, and is just entering the great ocean which lies before him in mysterious shadow, set before us the different stages of human life under images of which every beholder admits the beauty and deep significance. The second of this series, with the rich luxuriance of its foreground, its pleasant declivities in the distance, and its gorgeous but shadowy 'Structures in the piled clouds, is one of the most popular of Cole's compositions.

About this time Cole thought 'of painting Medora watching for the return of the Corsair, as related in Byron's poem, for a gentleman who had commissioned a picture, but who, after some reflection and discussion with his friends, abandoned the subject and adopted in its place one suggested by this stanza in Coleridge's admirable little poem of Love :

"She leaned against the armed man, The statue of the armed knight; She stood and listened to my harp Amid the lingering light."

This picture remains, I am told, among the things which he left unfinished at his death. Another work produced in 1840 was the Architect's Dream, an assemblage of structures, Egyptian, Grecian, Gothic, Moorish, such as might present itself to the imagination of one who had fallen asleep after reading a work on the different styles of architecture. The subject was in a measure forced upon him by the importunity of an architect, who seems to have imagined that he was able to give Cole some important hints in his art, and desired a work which should combine " history and landscape and the architecture of different st yles and ages." The painter, goodnaturedly, attempted to accommodate his genius to this caprice, but the picture produced did not satisfy the architect, who probably had no distinct idea of what be wanted, and who intimated his wish that Cole should try again. Cole wrote back in some displeasure, offering to return such compensation as he had received and to consider the commission as at an end. This I suppose, was done, as the picture is in the possession of one of the painter's relatives.

In July, 1841, Cole sailed on a second visit to Europe. On this occasion he travelled much in Switzerland, which he had never before seen, lingering as long as the limits of the time he had prescribed to himself would allow him in that remarkable country, and filling his mind with its wonders of beauty and grandeur. From Switzerland he passed to Italy, whence he made an excursion to the island of Sicily, with the scenery of which he was greatly delighted. On its bold rocky summits and in its charming valleys he found everywhere scattered the remains of a superb architecture, and gazed without satiety upon the luxuriance of its vegetation in which the plants of the tropics spring intermingled with those of temperate climes. In his letters, written from this island, he speaks with an enthusiastic delight of the abundance of flowers with which the waste places were enlivened: flowers which here we cultivate assiduously in our gardens, but which are shed profusely over the wildernesses of ancient but almost depopulated Sicily.

One of his pictures, I might place it among his earlier works, for it was painted before his first visit to Europe, strikingly illustrates the great delight he took in flowers. Some of those who hear me will doubtless recollect his picture of the Garden of Eden. In this work he attempted what was almost beyond the power of the pencil, a representation of the bloom and brightness which poets attribute to the abode of man in a state of innocence. In the distance were gleaming waters, and winding valleys, and bowers on the -gentle slopes of the hills; but nearer, in the foreground, the painter has lavished upon the garden a profusion of bloom, and hidden the banks and oppressed the shrubs with a weight of "flowers of all hues," as Milton calls these ornaments of his Paradise. A single flower, or a group of several, may be very well managed by the artist, but when he attempts to portray an expanse of bloom, a whole landscape, or any large portion of it, overspread and colored by them, we feel the imperfection of the instruments he is obliged to use, and are disappointed by the want of vividness in the impression he strives to create. The Eden of Cole has great merits as a scene of tranquil beauty, but there that in its design to which the power of the pencil was not adequate.

He saw other things, however, in Sicily. The aspect of Mount Etna seemed to have taken a strong hold on his imagination. Several views of it have been given by his pencil, one of which is in the exhibition of his works now open. A still larger one was painted by him some time after his return, which presented a nearer view of the mountain filling the greater part of the canvas with its huge cone. It was completed in a very few days, and was a miracle of rapid and powerful execution. It was not so generally admired as many of his works, and no doubt had in it some of the imperfections of haste; but for my part I never stood before it without feeling that sense of elevation and enlargement with which we look upon huge and lofty mountains in nature. With me, at least, the artist had succeeded in producing the effect at which he aimed. I have no doubt that he painted it with a mind full of the greatness of the subject, with a feeling of sublime awe produced by the image of that mighty mountain, the summit of which is white with perpetual snow, while the slopes around its base are basking in perpetual summer, and, on whose peak the sunshine yet lingers, while the valleys at its foot lie in the evening twilight.

Of course he passed some time at Rome in his second visit to Europe. In this old capital he produced a duplicate of the Voyage of Life. Thorwaldsen came to visit him. "These pictures," said the illustrious Dane, "are something wholly new in art. They are highly poetical in conception, and admirable in their execution."

In August, 1842, Cole returned to his family in Catskill.

In 1844 died Verbryck, one of the younger members of the Academy. He sleeps among the forest trees of Greenwood Cemetery, in a lowly spot chosen by himself, before his death, which would not attract your attention if you were not looking for it. There the grave of the modest and amiable artist is decked with flowering plants, set and tended by hands which perform the pious office when no one observes them. He was a painter of much promise, with a strong enthusiasm for his art and earnest meditation on its principles, but he was withheld by a feebleness of constitution from doing what his genius, if seconded by a more robust physical nature, would have given him the power to do. His productions, for the most part, have in them a shadow of sadness, as if darkened by the contemplation of that early fate which he knew to impend over him, and which took him away from a life that seemed to give him everything worth living for. It was not long before his death that in landing at Brooklyn from one of the ferry-boats, I met Cole, who said to me, "I have just paid a visit to Verbryck and looked over his sketches with him, in order that he might select one from which I am to paint a picture for a friend of his." On further conversation I found that a picture had been ordered of Verbryck, and the money advanced for it by the gentleman who is now president of the New York Gallery, and who knows how to be munificent without ostentation. At the time the commission was given, Verbryck hesitated at taking it, on account of the precarious state of his health, but Cole, who took great interest both in his personal character and his genius, advised him to accept it, and promised that if what he feared should come to pass, he would paint the picture in his stead. The dying artist we may suppose, was uneasy that he could not perform his engagement, and Cole had delicately renewed his offer. Verbryck selected a sketch of a quiet rural scene, such as might naturally be preferred by one in whose veins the powers of life were feebly struggling against disease, whose frame was languid while his blood was fevered, and to whom a serene and healthful repose would appear the most desirable of all conditions. This picture was afterwards executed, and forms the seventh in the collection now open to the public. It has no particular advantage of subject; a winding river, the Thames, flows tranquilly between sloping banks of green, and groups of trees overlook the waters. Yet it is painted with great care, for Cole was not a man to perform this act of piety in a slight and hurried manner; and the admirable disposition of objects and the perfect truth with which they are rendered, make it a work on which the eye dwells long without being weary. It is much prized by the owner, by whom it is regarded, I presume, as a memorial, not only of Cole's genius but of his goodness, and of that friendship between the two artists, which, interrupted for a brief space, is now doubtless renewed in another life.

Cole had never wrought with greater vigor nor after nobler conceptions than in the years which immediately preceded the close of his life. The admiration for his works, which I think had somewhat declined after his second visit to Europe, had revived. Such pictures as the Mountain Home, the Mountain Ford, the Arch of Nero, and many others, had recalled it in all its original fervor. A certain negligence of detail has been objected to some of Cole's works, produced in the maturity of his genius, but I have seen an artist, a painter of American landscapes, whose name will rank among those of the first landscape painters of the age, stand before the Arch of Nero, unable to find words for the full expression of that admiration with which he regarded the perfection of its parts, and the easy and happy dexterity with which they were rendered to the eye.

His last great work was the unfinished series of the Cross and the World, in which, as in many of his previous works, he sought to exemplify his favorite position that landscape painting was capable of the deepest moral interest and deserved to stand second to no other department of the art. Three only of the five pictures of which it was to be composed are finished, and in these we know not what changes in design or execution might have been made, had he lived to complete and harmonize every part of the design ; but that design is one of singular grandeur, and was capable, in his hands, of a noble execution.

To the second picture in this series I might object that it makes the life of the good man too much a life of pain, difficulty and danger. The path of his Pilgrim of the Cross is over steeps and precipices, interrupted by fearful chasms, amidst darkness and tempest, and torrents that threaten to sweep him from his footing, with no resting places of innocent refreshment nor intervals of secure and easy passage after the first asperities of the way are overcome. The most ascetic of those who have written on the Christian life hardly go this length. Even Bunyan provides for his Pilgrim the Delectable Mountains, and the fruitful and pleasant land of Beulah, and the hospitable entertainments of the House of the Interpreter. But in the third of the series I acknowledge a power of genius which makes me, for the moment, fully assent to Cole's idea of the dignity of his department of the art. That Pilgrim arrived at the end of his journey on the summit of the mountain, that ineffable glory in the heavens before which he kneels, the luminous path over the enkindled clouds leading upward to it, the mountain height shooting with verdure under the beams of that celestial day, the darkness sullenly recoiling on either side, the ethereal messengers sent to conduct the wayfarer to his rest, form altogether a picture which could only have been produced by a mind of vast creative power quickened by a fervid poetic inspiration. The idea is Miltonic, said a friend when he first beheld it. It is Miltonic; it is worthy to be ranked with the noblest conceptions of the great religious epic poet of the world.

It was while he was engaged in painting this series that the summons of death came. An inflammation of the lungs, a sudden and brief illness, closed his life on the 13th of February. On the third day after the attack he despaired of recovery and began to make preparations for death. The close of his life was like the rest of it, serene and peaceful, and he passed into that next stage of existence, from which we are separated by such slight and frail barriers, With unfaltering confidence in the divine goodness, like a docile child guided by the kindly hand of a parent, suffering itself to be led without fear into the darkest places.

His death was widely lamented. How we were startled by the first news of, it, which we refused to believe, it came so suddenly, when we knew that a few days before he was in his highest vigor of body and mind, resolutely laboring on great projects of art, and we looked forward to a long array of years for one who lived so wisely, and for whom so splendid a destiny on earth seemed to be ordained! On the little community in which he lived, the calamity fell with a peculiar weight. The day of his funeral was a solemn day and a sad one in Catskill; the shops were closed and business was suspended in obedience to a common feeling of sorrow.

For that sorrow there was good cause; for in Cole there was no disproportion between the cultivation of his moral and that of his intellectual character. He was unspotted by worldly vices, gentle, just, beneficent, true, kind to the unfortunate, quick to interfere when wrong or suffering were inflicted on the helpless, whether on his fellow-man or the brute creation. His religion, fervently as it was cherished, was without ostentation or austerity, not a thing by itself, but a sentiment blended and interwoven with all the actions of his daily life. His manners were cheerful, even playful, and his ready ingenuity was employed in various ways to promote the innocent amusements of the neighborhood in which he lived. I remember asking one of his relatives for some examples of his goodness of heart. "His whole life," was the reply, " seemed made up of such examples; he never appeared to be in the wrong; he never did anything. which gave us offence or caused us regret. We delighted to have him always with us; we were sorry whenever be left us and glad when he returned." He is now gone forth forever; gone forth to gladden his friends no more with his return; the home which was brightened by his presence is desolate, the sorrow for his absence is perpetual.

Of his merits as an artist I ought to express an opinion with diffidence, standing before you as I do, a stammerer among those who speak the true dialect of art. Let me say, however, that to me it seems that he is certain to take a higher rank after his death than was yielded to him in his life. When I visit the collection of his pictures lately made for exhibition; when I see how many great works are before me, and think of the many which could not be brought into the collection; when I consider with what mastery, yet with what reverence he copied the forms of nature, and how he blended with them the profoundest human sympathies, and made them the vehicle, as God has made them, of great truths and great lessons, when I see how directly he learned his art from the creation around him, and how resolutely he took his own way to greatness, I say within myself, this man will be reverenced in future years as a great master in art, he has opened a way in which only men endued with rare strength of genius can follow him. One of the very peculiarities which has been objected to him as a fault, a certain crudeness, as it has been called, in the coloring, appears to me a proof of his exquisite art. He did not paint for this year or for the next, but for centuries to come ; his tints were so chosen and applied that he knew they would be harmonized by time, and already in several of his paintings that hoary artist has nearly completed the work which the painter left him to do.

Reverencing his profession as the instrument of good to mankind, Cole pursued it with an assiduity which knew no remission. I have heard him say that he never willingly allowed a day to pass without some touch of the pencil. He delighted in hearing old ballads sung or books read while he was occupied in painting, seeming to derive, from the ballad or the book, a healthful excitement in the task which employed his hand. So accustomed had he grown to this double occupation that he would sometimes desire his female friends to read to him while he was writing letters. In the contemplation of nature, however, for the purposes of his art, I remember to have heard him say that the presence of those who were not his familiar friends, disturbed him. To that task he surrendered all his faculties, and no man, I suppose, ever took into his mind a more vivid image of what he beheld. His sketches were sometimes but the slightest notes of his subject, often unintelligible to others, but to him luminous remembrancers from which he would afterwards reconstruct the landscape with surprising fidelity. He carried to his painting room the impressions received by the eye and there gave them to the canvas; he even complained of the distinctness with which they haunted him. "Have you not found," said he, writing to a distinguished friend, "I have, that you never succeed in painting scenes, however beautiful, immediately on returning from them? I must wait for time to draw a veil over the common details, the unessential parts, which shall leave the great features whether the beautiful or the sublime, dominant in the mind."

He could not endure a town life; he must live in the continual presence of rural scenes and objects. A country life he believed essential to the cheerfulness of the artist and to a healthful judgment of his own works; in the throng of men he thought that the artist was apt to lean too much on the judgment of others, and to find their immediate approbation necessary to his labors. In the retirement of the country, he held that the simple desire of excellence was likely to act with more strength and less disturbance, and that its products would be worthier and nobler. He could not bear that his art should be degraded by inferior motives. "I do not mean," said he, not long before his death, "to paint any more pictures with a direct view to profit."

There are few, I suppose, who do not recollect the lines of Walter Scott, beginning thus:

"Call it not vain ; they do not

err

Who say, that when the poet dies,

Mute nature mourns her worshipper,

And celebrates his obsequies."

This is said of the poet; but the landscape painter is admitted to a closer familiarity with nature than the poet. He studies her aspect more minutely and watches with a more affectionate attention its varied expressions. Not one of her forms is lost upon him; not a gleam of sunshine penetrates her green. recesses; not a cloud casts its shadow unobserved by him; every tint of the morning or the evening, of the gray or the golden noon, of the near or the remote object is noted by his eye and copied by his pencil. All her boundless variety of outlines and shades become almost a part of his being and are blended with his mind.

We might imagine, therefore, a sound of lament for him whom we have lost in the voices of the streams and in the sighs, of the wind among the groves, and an aspect of sorrow in earth's solitary places; we might dream that the conscious valleys miss his accustomed visits, and that the autumnal glories of the woods are paler because of his departure. But the sorrow of this occasion is too grave for such fancies. Let me say, however, that we feel that much is taken away from the charm of nature when such a man departs. To us who remain, the region of the Catskills, where he wandered and studied and sketched, and wrought his sketches into such glorious creations, is saddened by a certain desolate feeling, when we behold it or think of it. The mind that we knew was abroad in those scenes of grandeur and beauty, and which gave them a higher interest in our eyes, has passed from the earth, and we see that something of power and greatness is withdrawn from the sublime mountain tops and the broad forests and the rushing waterfalls.

Withdrawn I have said, not extinguished, translated to a state of larger light, and nobler beauty and higher employments of the intellect. It is when I contemplate the death of such a man as Cole under such circumstances as attended his, that I feel most certain of the spirit's immortality. In his case the painful problem of old age was not presented, in which the mind sometimes seems to expire before the body, and often to wither with the same decline. He left us in the mid-strength of his intellect, and his great soul, unharmed and unweakened by the disease which brought low his frame, amidst the bitter anguish of the loved ones who stood around him, when the hour of its divorce from the material organs had come, calmly retired behind the veil which hides from us the world of disembodied spirits.

Writings of his Contemporaries

William

Cullen Bryant

Washington

Irving

Thomas

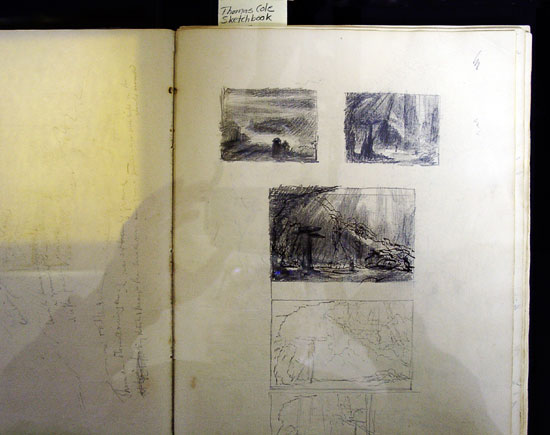

Cole's 1827 Sketchbook

A Look Inside